MEMORIALIZATION AND MEMORY OF THE BENGAL FAMINE OF 1943

Spring 2025 Capstone by Anika Sultana (Visual & Performing Arts – Art History)

The University of Texas at Dallas

Works by Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad

Bhattacharya, and Somnath Hore.

This site is best viewed on a PC.

In the canon of world history, famine memorialization has taken form in several fashions, whether it be led by government efforts or through locally-led art and literature. The degree of famine memorialization, however, varies from location to location. For example, in Ireland, the Great Hunger, which saw the death of 1 million people and the immigration of over 1.5 million people from Ireland, has museums dedicated to the Great Hunger, a national day of commemoration, and several other monuments to the event, some of which extend outside of Ireland and into the United States. Among these institutionally-supported initiatives, there also exists an established sense of both chronistic and contemporary visual culture surrounding the famine; objects like sculptures and plaques are embedded into Ireland’s cityscape, acting as visual cues of remembrance to reinforce a sense of “cultural memory” among the Irish people. The regions of Bangladesh and West Bengal, in contrast, do not preserve or showcase similar methods of institutionally-supported memorialization for the Bengal Famine of 1943, an event which claimed 3 million lives. Unlike Ireland, efforts like a day of remembrance, commemorative museums, or a public visual culture to maintain the Bengali people’s “cultural memory” of the famine do not exist in these regions, especially in modern-day Bangladesh, which this analysis focuses on.This paper seeks to analyze the memorialization efforts of the Bengal Famine of 1943, to visit the art and literature that has been produced as a result of the famine, and to understand how artists’ work — namely that of Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Zainul Abedin, and Somnath Hore — shape the Bengali memory of the famine, particularly in Bangladesh’s modern memory. In particular, this paper will also bring forth the question of why the Bengal Famine of 1943 has not been afforded the same amount of attention as famines like the Great Hunger of Ireland. It will also explore how the reaction to the Bengal Famine of 1943 has impacted the Bengali people’s post-famine reactionary behaviors to similar types of politically-charged events in Bangladesh’s history.To read this paper in full-length, click here.

BACKGROUND

ABOUT THE FAMINE ARTISTS

CULTURAL MEMORY

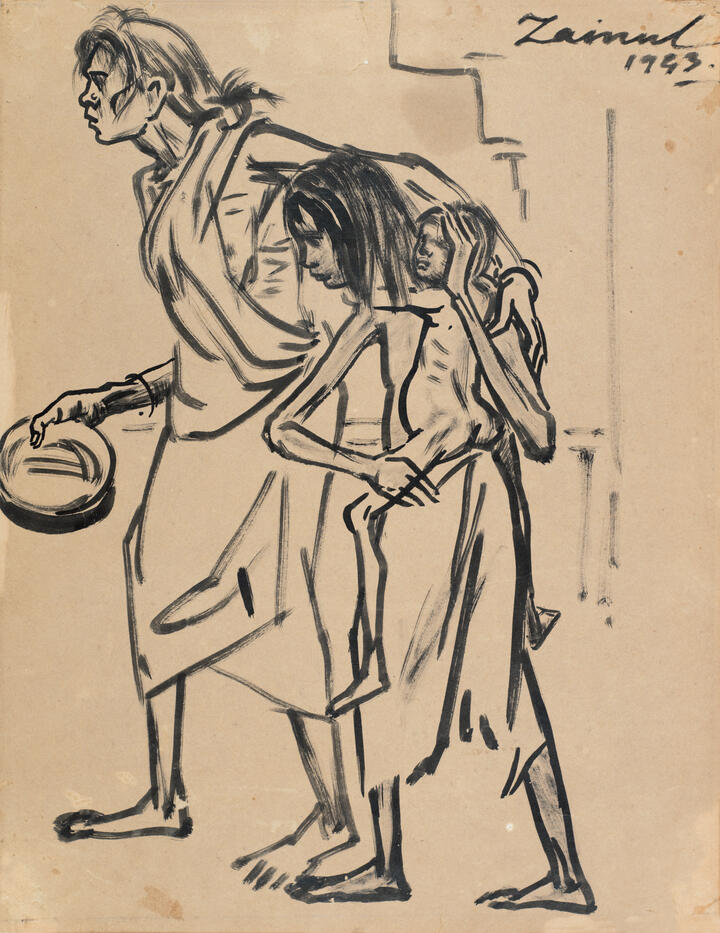

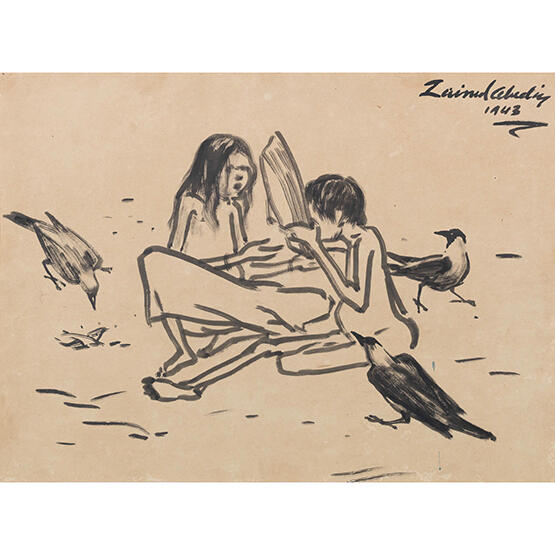

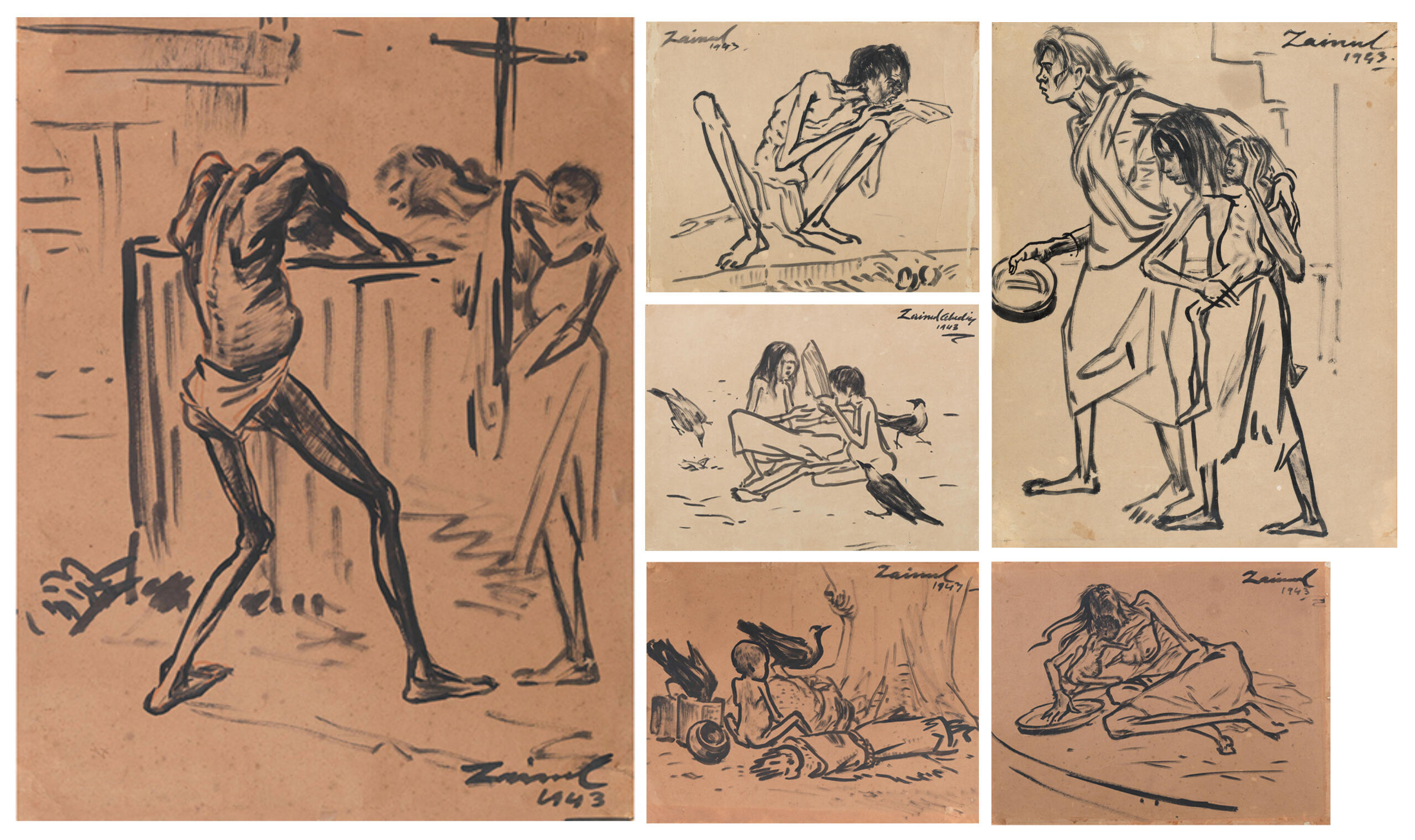

Work by Zainul Abedin

Scholar Jan Assmann defines “cultural memory” as the overall summation of meaning between three key actors in memorialization:

• “mimetic” memory, or that of action;

• the memory of tangible objects; and

• communicative memory, which involves the language used to discuss certain events.When discussing the Great Hunger of Ireland and the Bengal Famine of 1943, both famines involve all three facets, especially through the vessels of art and literature. Through such channels, both famines are understood to be a type of “mass-atrocity” because they harmed people to such a major extent; therefore, the affected peoples’ memories are sustained by a collective group of individuals, and are grieved in a crowd-like manner. The memory of these famines can then be used as a tool for the political unification of said affected peoples, as the process of memory-making grants people the “power” of honor and remembrance in a larger narrative. Both famines also contribute to the broader theory of “memory culture,” where social groups base the group’s identity and image around a universal understanding of certain memories.Cultural memory is something both Ireland and Bangladesh grapple with, as both suffered loss under the British government. However, while Ireland’s cultural memory is platformed and regarded as an upkeep of tradition, so as not to forget the famine, Bangladesh’s cultural memory is discounted or largely ignored by global powers in the “center” as a method to actively marginalize the country and its people. One could also argue that, with the precedent of the British Raj — where the Bengal region had to financially depend on Britain from 1858 to 1947 — the lack of famine memorialization occurred as a method of keeping the country “in line” with its historical dependency on the west. In recent times, Bangladesh’s economic capital has improved, with its per capita income increasing beyond that of India’s as of October 2020, so one could pose the argument that as Bangladesh’s dependency on the west weans, Bangladesh’s independence — both financial and cultural — could grant the country with the (cultural) authority to pursue memorialization efforts.

FAMINE MEMORIALIZATION: IRELAND VS. BANGLADESH

Ireland has sculptures, plaques, a national day of commemoration, and museums like the National Famine Museum and Ireland's Great Hunger Museum of Fairfield. You can view some of the Great Irish Hunger's commemorative sculptures here.Modern-day Bangladesh currently lacks this type of commemorative infrastructure, with no government or major institution leading any efforts to visually remember the famine. Work from key artists like Zainul Abedin, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, and Somnath Hore prove that there were active members of society documenting the famine, which begs the question: why wasn't the Bengal Famine of 1943 afforded the same amount of attention as the Great Irish Hunger?In the essay "Remembering/Forgetting Hunger: Towards an Understanding of Famine Memorialisation," Camilla Orjuela poses several theories:

• Culpability shapes how individuals/states (fail to) address the famine and its victims, to where forgetting is a form of humiliated silence.

• Mass-starvation can be one of many traumas endured by a society, leading to an "entanglement" of traumas.

• Memories of other traumas can sometimes inspire and impede upon famine memorialization.

• Initiatives “from below” can affect methods of famine memorialization, in that many societies see “the erosion of the central authorities’ dominant position in constructing commemorative practices.”

Work by Zainul Abedin

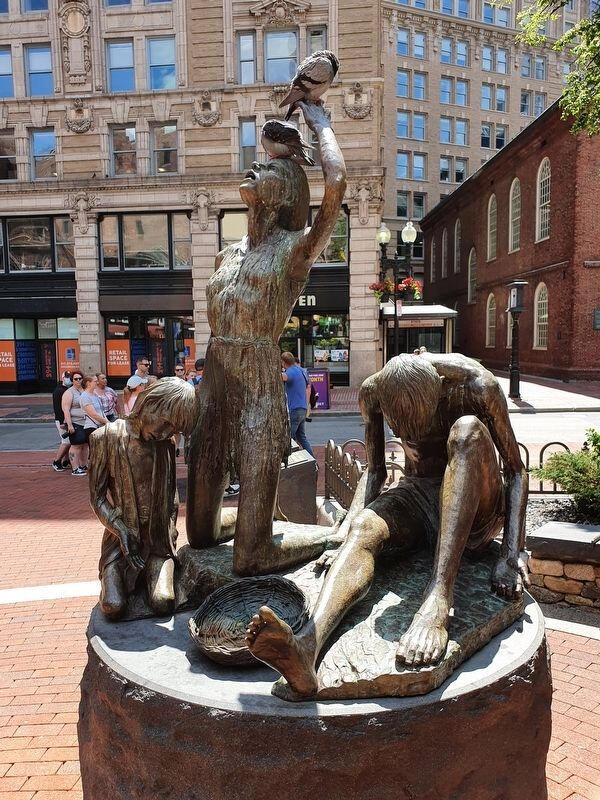

THE GREAT IRISH FAMINE

In contrast to the Bengal Famine, the Great Hunger of 1845 to 1852, which saw the death of 1 million people — a third of the death count of the Bengal Famine — was caused by the fungus Phytophthora infestans. The fungus destroyed the potato crop — upon which the Irish population had become nutritionally dependent — in what was officially called the “late blight.” The famine caused vitamin C and A deficiency, hunger edema, nutritional marasmus, “famine fever” (a mix of typhus and relapsing fever), along with diarrhoeal illnesses, dysentery, and cholera. The British government’s response, unlike that with the Bengal Famine, was initially prompt under the ministership of Sir Robert Peel, but after being succeeded by the Whig prime minister Lord John Russell, the government response became inadequate as the Whig administration was influenced by the prevailing laissez-faire doctrine. Emigration was then seen as a form of escape for the Irish, with 75% of immigrants leaving Ireland and settling in the U.S.With this knowledge in mind, commemoration efforts for the Great Hunger have extended both into Ireland and past Ireland. For example, in the United States — where immigration was catalyzed by the famine — the Boston Irish Memorial, the Irish Hunger Memorial in New York, and the Irish Memorial in Philadelphia all serve as high-traffic beacons for commemoration.

Left: Boston Irish Memorial, The Historical Marker Database

Middle: Irish Hunger Memorial in New York, Wikipedia

Right: Irish Memorial in Philadelphia, Association for Public Art

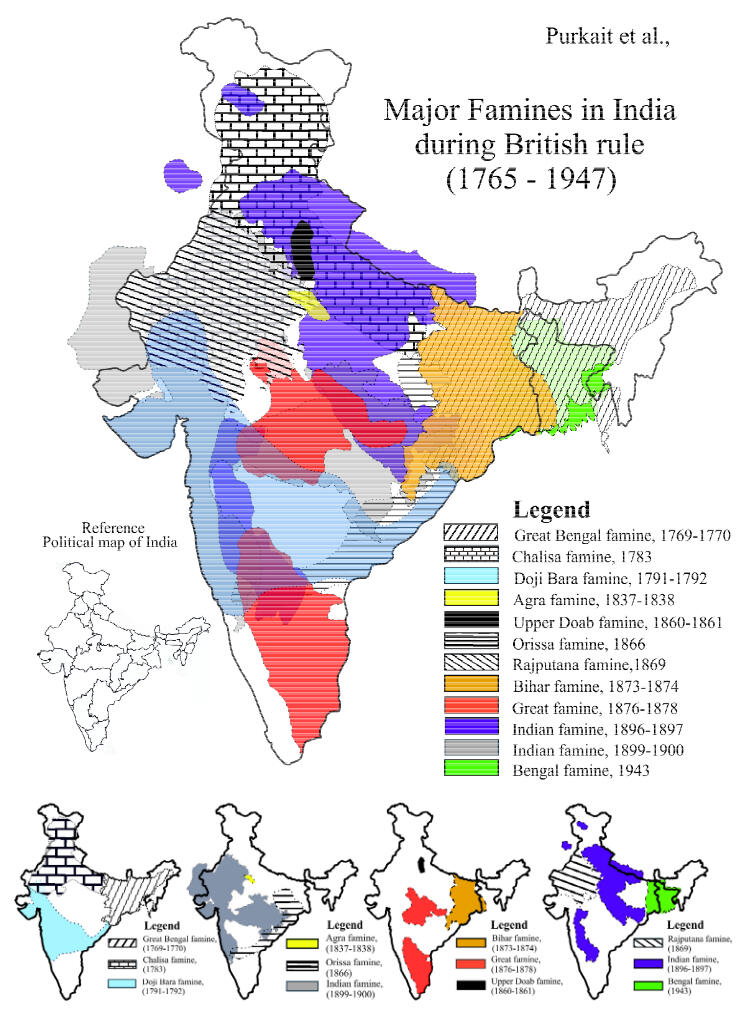

THE BENGAL FAMINE OF 1943

Left: Map depicting contemporary borders of West Bengal and Bangladesh, courtesy of Reece Jones.

Right: Map depicting 12 (of 25) major famines during British rule, courtesy of Purkait et al.

BENGAL

As a region, “Bengal” is located in the northeastern portion of the Indian subcontinent. Although there was a first partitioning of Bengal in 1905 into East Bengal (for Muslims to inhabit) and West Bengal (for Hindus to inhabit) in 1905, historically speaking, the 1947 partition of India allowed the two regions to devolve into the state of West Bengal (which became part of India) and Pakistan (which was divided into East and West Pakistan). After the Liberation War of 1971, East Pakistan became modern-day Bangladesh. The use of the term “Bengal” in this paper refers to the states of West Bengal and modern-day Bangladesh, including Calcutta (now Kolkata, today’s capital of West Bengal).Famines frequently occurred throughout South Asia, but Bengal specifically was often affected most severely by famines, with common causes among early famines including droughts, failure of crops, cyclonic weather, and British policy failures surrounding grain exports. Until the establishment of colonial censuses in the 1860s, demographic characteristics in the pre-colonial period could not be accurately analyzed due to low literacy rates, lack of censuses, and a lack of modern record-keeping systems (although, according to scholar Senjuti Mallik, approximately 25 major famines occurred under the British Raj).

THEORY VS. PRACTICE

In theory, the Bengal Famine of 1943 was initially seen as a product of natural phenomena, with the Malthusian theory of overpopulation and the Darwinian theory of natural selection used to support racist thinking among government figureheads like Winston Churchill. Churchill’s racism was not unknown: for example, he claimed that the Indian population was “the beastliest in the world after the Germans” and argued that the famine itself was self-inflicted by the Indian population, where, as a result, “Indians should pay the price for their negligence.” The Famine Inquiry Commission, appointed by the British-Indian government, further upheld Churchill’s sentiments and maintained a Malthusian view of food shortages, blaming natural disasters along with “the tendency of Indians to breed excessively.” The FIC also grossly numbered the death toll, initially placing it at about 1.5 million. Wallace Ruddell Aykroyd, nutrition expert and member of the FIC, would later state that this figure was an underestimate. Aykroyd also acknowledged the FIC’s official preferences for euphemisms like “food shortage” and “distress” over direct terminology like “famine” in the FIC’s language surrounding the famine.In practice, the general agreement of the “cause(s)” of the famine among scholars include a deficit in production of food due to a loss of imports from Burma, which Japan had captured at the time; the “material and psychological consequences” of World War 2 leading to an increase in the price of rice; the incompetence of the Bengal government in controlling the supply and distribution of food grains in the market, leading to large-scale hoarding; and overall delayed responses from the Indian and British governments. Cyclone and flooding conditions in West Bengal further exacerbated conditions. Furthermore, precautionary scorched-earth policies were set in place in the face of a Japanese threat, leading to policies like the Boat Denial Policy and Rice Denial Policy being integrated; the former destroyed 66,000 boats and the income of thousands of peasants, and the latter re-distributed 40,000 tons of grains to solely urban military or industrial workers.

BENGAL & THE EAST INDIA COMPANY

After having to implement such drastic policies in a region with less-than-favorable environmental conditions, one may question why the British decided to concentrate on an area like Bengal (or the Indian subcontinent).To situate the British’s arrival within the region, the British’s motivations were primarily economic.

• The East India Company’s royal charter was granted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, granting the EIC the exclusive right to trade with India.

• The company’s first trading post was then set up in the western port of Surat in 1607, allowing the EIC to participate in “triangular trade,” where precious metals were exchanged for Indian goods (like fine textiles); said Indian goods were then sold in the East Indies in exchange for spices, which were shipped back to London in order to make a profit on the original investment on the precious metals.

• After the Battle of Buxar in 1764-65, the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II also granted the EIC the right to collect land revenue in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, making regions like Bengal specifically favorable as a port of operations for the company.Collecting land revenue from Bengal would further allow the EIC to expand both economically and politically, with the EIC becoming a channel of imperial operation for the British in India, For example, in 1760, the EIC had 6,680 troops; by 1823, this number would expand to 129,473, with the majority of troops being recruited from Indian peasantry.Although the company was eventually dissolved in 1874, the decline of the company essentially catalyzed the formation of the British Raj, or the period of direct British rule over the Indian subcontinent. As events like the 1857-58 Sepoy Mutiny (or the First Indian War of Independence) were suppressed by the British Crown, the Crown seized the EIC’s territories in 1858 and continued to extract resources from the subcontinent until 1947.

"East Indiamen in a Gale" by Charles Brooking (ca. 1759)

BENGALI ARTISTIC CULTURE

If the Great Hunger of Ireland is worthy of such memorialization, we must then consider how the Bengal Famine is remembered, both by the cultural group preserving the memory of the famine — in this case, the Bengali people — and by the broader institution(s) enacting memorialization efforts for the famine.In Bengali tradition, the famine has been memorialized through a wide variety of mediums, including theater, literature, and art. With a rich history of political awareness and resistance to colonial rule among contemporary creatives, the Bengal Famine inspired creators of the 1920s and 1930s to shift towards realism, taking up sociopolitical and economic exploitation as themes for their creations.In the realm of literature and theater, the Progressive Writers’ Association and Indian People’s Theater Association were respectively founded in 1936 and 1943 as strong Communist instruments of protest against colonial rule. Specifically, these groups formed to condemn the rise of fascism in Japan and Europe, especially after the August 1942 resolution of the “Quit India” movement, which demanded the end of British colonial occupation. Plays like Bijon Bhattacharya’s “Nabanna” (1944) were influential in drawing attention to the rural-urban divide created as a result of the famine, where middle and upper-class Bengali were greatly detached from the turmoil created by the famine.Novels and short stories also sought to highlight the shortcomings and misery of rural Bengal during the famine as a means of social justice. Namely, works like Freda Bedi’s Bengal Lamenting (1944) and Ela Sen’s Darkening Days (1944) served as documentation of living conditions, often dramatizing the individual’s experience with the famine. Freda’s work is a first-hand account of the famine, while Sen’s work is a half-fictionalized account that particularly surrounds the narrative of female victims and sex workers, though one chapter also focuses on “Facts and Figures” surrounding the famine. Upon release, Sen’s book was banned for a year, then published with heavy censorship in 1945.

Dedication from "Darkening Days" by Ela Sen (1944)

In the realm of visual arts, artists saw the intertwining of political activism and artistic creation. For example, the All India Students’ Federation attempted to bring together artists without political affiliations and those affiliated to the Communist Party of India in 1944. As a result, the Bengal Painters’ Testimony was published, consisting of art solely dedicated to the Bengal Famine — the volume did not follow a strict theme, style, or method of art, but each copy was sold at 5 rupees to raise funds. The testimony saw a mix of artists from different schools of thoughts, as well as a mix of Indians, Europeans, Hindus, and Muslims. Other unaffiliated groups like the Calcutta Group also formed to depict the famine through experimental art forms, like that of Expressionism and Cubism.

Work by Chittaprosad Bhattacharya

THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA

During this time, the Communist Party of India dominated major spheres of Bengali-led cultural and social discussion, especially of those surrounding the famine.The party was officially founded in 1925. Prior to the famine, the party, with an audience mainly consisting of the urban working class, focused on acts of social justice like disengaging India’s developing civil disobedience movements from 1930-31 and 1932-34, denouncing them as “bourgeoisie, reactionary, and calculated to distract the Indian masses from the real struggle, presumably led by the Communists themselves.”Politically, the party was also active in organizing the masses against Nazi Germany and Japanese fascist sentiments during World War 2, supporting the Allied Powers’ war efforts, and maintaining a general anti-colonial stance.In general, however, the party’s activity was met with hostility from the British and Indian governments — the Meerut Conspiracy Case of 1929-1933 led to the arrests of almost all of the prominent Communists at the time, and by 1934, the Government of India banned the Communist Party on the basis that the party and its branches “interfered with the administration of law and constituted a danger to public peace.”

Despite the pushback, the party and its members remained active. In the process of “harvesting motifs from folk tales and mythologies, repurposing popular tropes of resistance and rubbing together different ideas of labour and craft, [and] art and politics,” as scholar Raymond Williams says, the party used alternative means like drama, art, and literature to create awareness of colonial exploitations, with the Progressive Writers’ Association and the Indian People Theater’s Association acting as the party’s main conduits for such activity. The party further initiated cultural dialogue by commissioning artists and painters to portray the suffering and frustration of the common people.One such CPI-affiliated artist was Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915-1978), whose work was mostly limited to the party’s political purposes. To learn more about Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, click here.

CHITTAPROSAD BHATTACHARYA

Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915-1978) was an artist affiliated with the Communist Party of India.In 1937-1938, Bhattacharya came into contact with the Communist Party and joined in 1940; he was active in the cultural front and the IPTA in particular, writing songs and taking part in performances. However, Bhattacharya was most known for his drawings, which were shown in Janayuddha, the CPI’s Bengali organ, and People’s War, the CPI’s English weekly paper.The pinnacle of his work can be found in his English travel report, Hungry Bengal: A Tour Through Midnapore District, where Bhattacharya extensively travelled throughout rural Bengal and highlighted black-marketing and exploitation of the poor during the famine. The travel report consists of 22 drawings where Bhattacharya carried string-bag paper and a pen and committed to a style of social realism, which “was aimed at breaking the social alienation of the disillusioned contemporary Bengali middle-class” with “brutally honest sketches.” Hungry Bengal was subsequently banned by the government, where five thousand copies were destroyed by the government. One or two copies of the report managed to escape, with one copy being preserved by the family as the source for a reprint.As termed by scholar Nikhil Sarkar, all three artists — Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Zainul Abedin, and Somnath Hore — continued to document “mass experiences” that occurred after the famine, including that of partition and other activism efforts. In Bhattacharya's case, he recorded the Telengana peasant uprising from 1946 to 1948 as his second “mass experience.” As all three artists dealt with these various “mass experiences,” they also channeled their work through various mediums. For example, Bhattacharya was also known for working with woodcut and linocut prints.

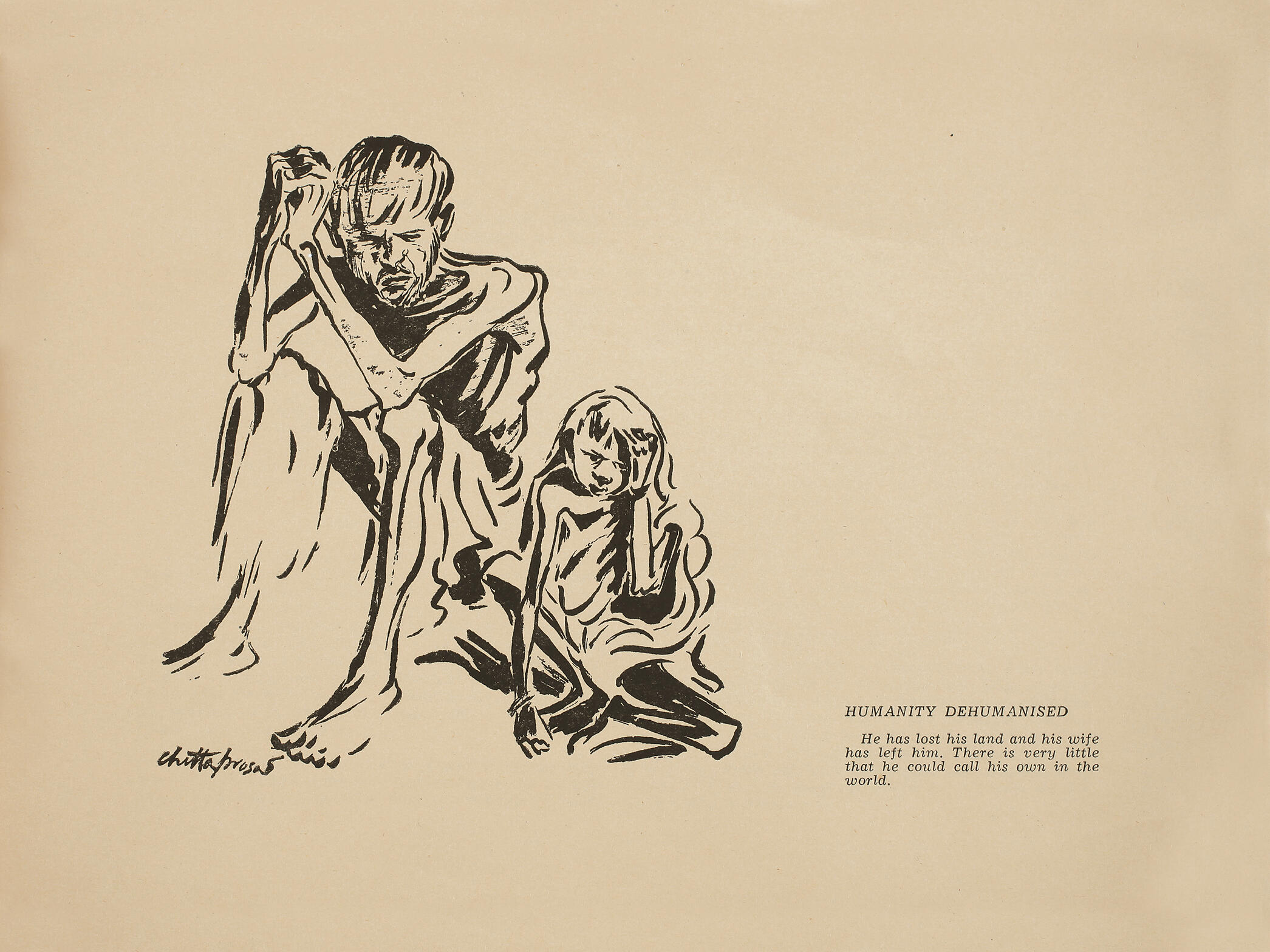

Page from the only surviving copy of the self-published "Hungry Bengal," ink on paper, 1945. (Reproduced in facsimile by DAG Modern, New Delhi, 2011. Image taken from “So Many Hungers.”)

In viewing the sketch above, the sketch above uses a contour-heavy style to presumably depict an adult and a child, possibly father and child, in blank space, emphasizing their lack of worldly property and their focus on survival. The adult figure assumes a sitting position, hands clasped in beggar formation (or potentially in prayer, to plead with a higher being and ask for help) with a stern, broken expression on his face. The child, whose gaze is similarly jaded, is swallowed whole by cloth that surrounds them, further emphasizing the child’s poor health and stature. This sketch also includes text that reads, “HUMANITY DEHUMANISED: He has lost his land and his wife has left him. There is very little that he could call his own in the world.” The narrative depicted in these realist, black-and-white sketches are ones of desolation and loss; they are intended to alert viewers to typical famine scenes that would play out on streets and on land, as if to question the viewer’s own humanity and challenge the middle-class Bengali’s “repressive erasure” of the famine.

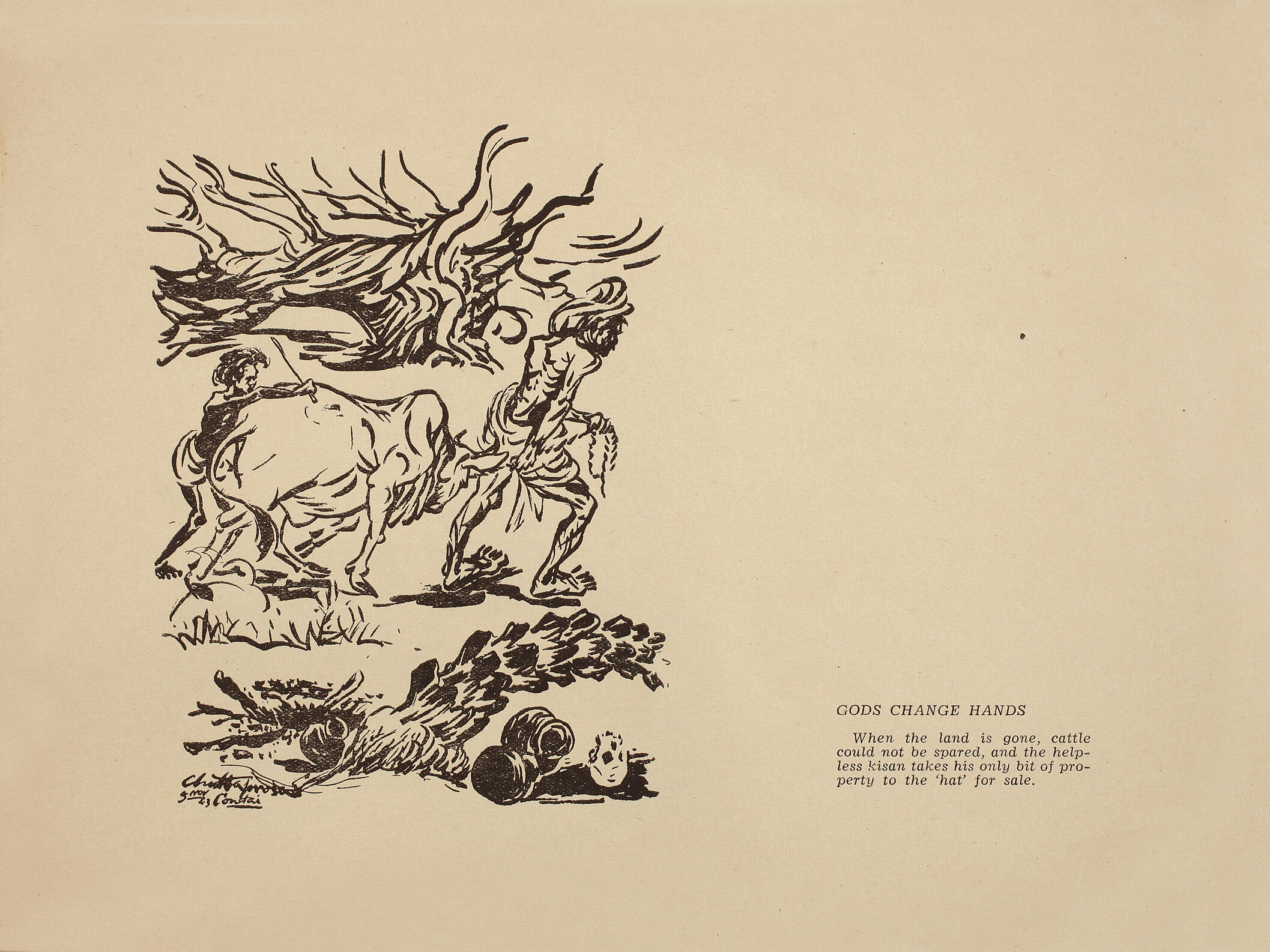

Page from the only surviving copy of the self-published "Hungry Bengal," ink on paper, 1945. (Reproduced in facsimile by DAG Modern, New Delhi, 2011. Image taken from “So Many Hungers.”)

Similarly, Bhattacharya equips fluid ink-strokes in an expressionist-like style to depict an emaciated, struggling-yet-persisting body in transit and a sparse environment in profile view. In the foreground, coveted crops and a skull are visible. It could be argued that the inkwork in profile view is intended to anonymize the struggling subject, though snippets of text alongside the image contextualize the scene at hand. For example, the text reads, “GODS CHANGE HANDS: When the land is gone, cattle could not be spared, and the helpless kisan [agricultural peasant] takes his only bit of property to the ‘hat’ for sale.” Scholar Nikhil Sarkar notes that having faces and bodies turn away from the canvas risks erasing the identities and agency of the represented subjects, but the written component of Bhattacharya’s travel report allows him to document sights, smells, and inconveniences of the famine that cannot be documented through sight alone, grounding the experiences of the figures being captured on paper.

Hungry Bengal allowed for a relationship between the visual and the verbal to thrive, where Bhattacharya, as the subjective writer, could convey objective documentation. Bhattacharya would overall be known as an observer who “shaped for Bengali the trend of a more humane kind of reporting,” different from “the impersonal, dry and pragmatic idiom of bureaucratic officialese” from the Communist Party’s organs at the time.

Various linocuts on paper. (Images courtesy of Akar Prakar Gallery.)

ZAINUL ABEDIN

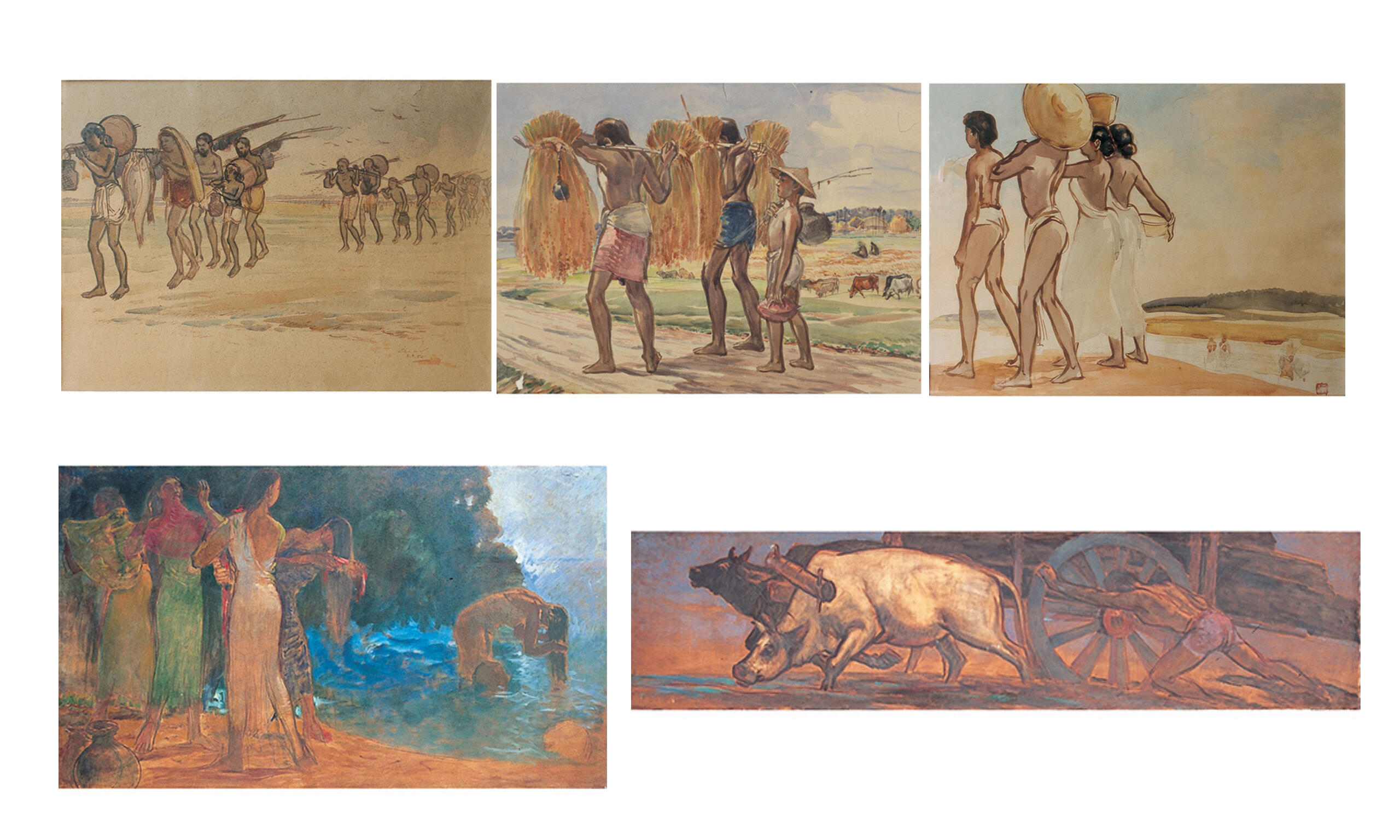

Born in East Bengal, Zainul Abedin (1914-1976) grew up with picturesque scenes from the Brahmaputra River basin and began his artistic career as an Impressionist landscape painter. He completed his degree from the Government College of Art in Calcutta in 1938 and became a lecturer at the college when he was 29. However, with the onset of the famine, Abedin left his job to document the sights surrounding him through his well-known famine sketches.The famine signaled a shift in Abedin's style, pivoting from that of academic painting to social realism. His work prior to the famine and during the famine poses a stark contrast against one another: his earlier works depict naturalistic pastoral scenes in Bengal, with gentle color washes in a European-influenced academic style, while his famine sketches, done with the cheapest paper and ink available, are visceral and undisguised in nature. Using choppy and angular brush strokes, the sketches explicitly depict famine scenes of suffering, pain, and desperation. Furthermore, the depictions of near-skeletal bodies alongside scavenger-class animals, the general lack of facial expressions, the disheveled nature of the subjects, coupled with a lack of spatial construction — similar to the lack of environment seen in Bhattacharya’s works — emphasize the dreadful nature of the famine.Eleven of Abedin’s famine sketches were selected for use in Ela Sen’s Darkening Days, creating an enriched visual and literary narrative about the famine for readers.As termed by scholar Nikhil Sarkar, all three artists — Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Zainul Abedin, and Somnath Hore — continued to document “mass experiences” that occurred after the famine, including that of partition and other activism efforts. In Abedin's case, he continued incorporating motifs of toil and anguish in his work through works like Nabanna (1970) and Monpura'70 (1970), with both pieces acting as attempts to process long-term trauma.

Various pre-famine works, watercolor and oil paint, ca. 1930s. (Courtesy of The Bengal Foundation.)

Various famine sketches, ink on paper, ca. 1943. (Courtesy of The Bengal Foundation.)

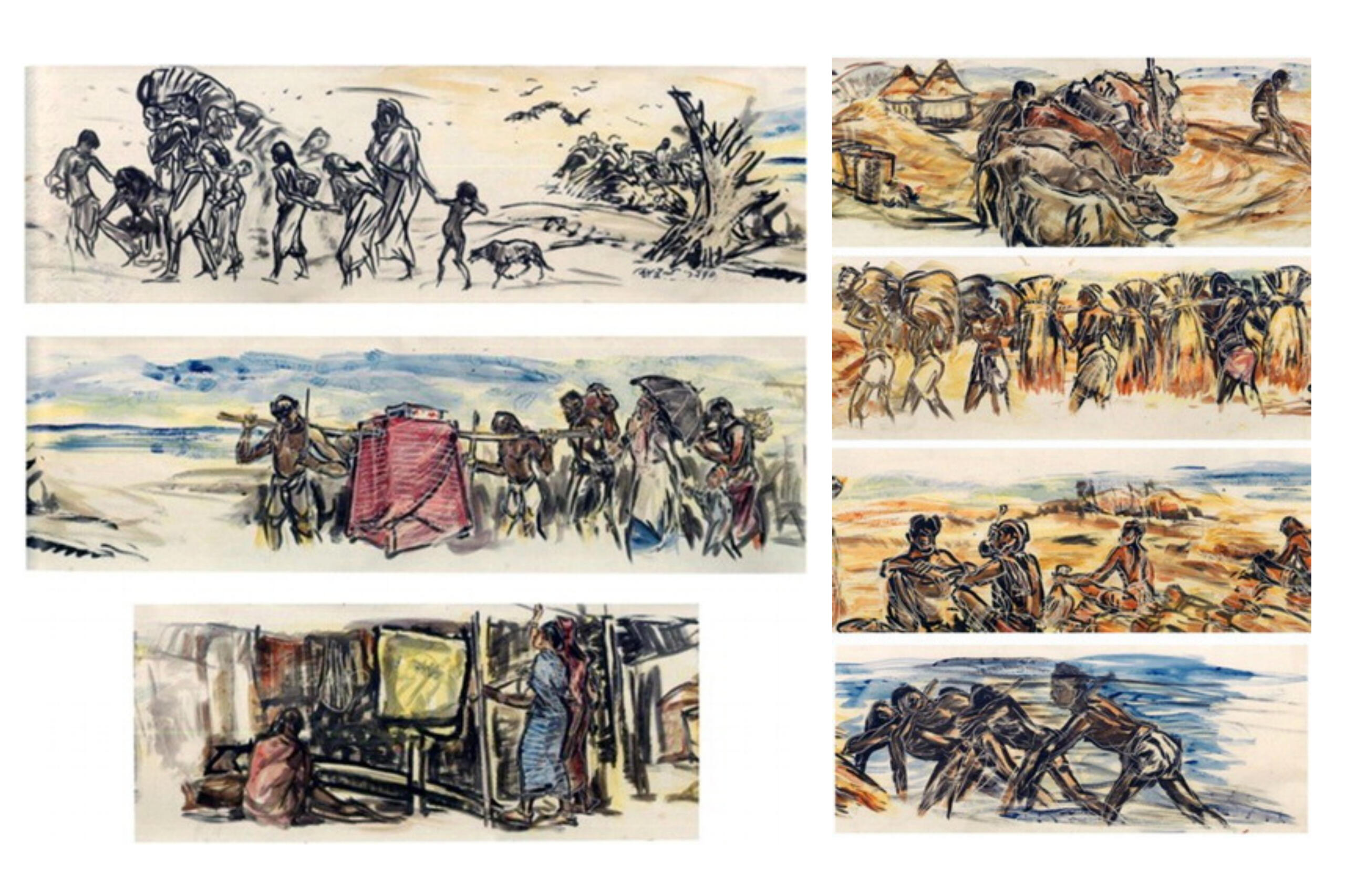

Details from "Nabanna," wax, black ink and watercolor, 1970 (Courtesy of Bangladesh National Museum, Dhaka. Image taken from “Shadow-Lines: Zainul Abedin

and the Afterlives of the Bengal Famine of 1943.”)

Painted in February of 1970, Nabanna, Bangla for “festival of new harvest,” is a 65-inch long scroll that was painted to commemorate the annual harvest festival set up by Abedin at the Dhaka Art Institute. The work is also based on a play of the same name written by Bijon Bhattacharya during the famine years, which depicts a starving Bengali peasant, who, like many others during the famine, had to uproot their life and migrate to urban Calcutta. Nabanna is composed in chapter-like panels in three key segments, with the first depicting villagers trudging through an emaciated landscape, the second showing a return (often being called “Life in Bangladesh” or “Bride Returning to Her Parent’s Home”), and the third showing the collective tilling of earth amid a bountiful harvest.In Nabanna, Abedin uses a cycle of “life” — struggle, labor, and reclamation — to situate the common Bengali experience within multiple political happenings, bridging together multiple lines of cultural memories. Considering this work was also made in 1970, thirty years after the famine, this work is meant to consolidate the trauma felt during events like the famine and the 1947 partition. This work also serves as a prelude to Bangladesh’s independence, as it was created before the bloody Liberation War and genocide in 1971. With this in mind, scholar Sanjukta Sunderason posits the idea that Nabanna serves as a metaphor for a “metaphoric harvesting of struggle,” as if to say that after suffering such hardship and loss, the Bengali people’s efforts to survive and resist suppression have finally been recognized; it is a reinforcement of the Bengali people’s cultural memory.Monpura’70, another scrollwork produced by Abedin (after a coastal storm off the island of Monpur killed thousands of people in November of 1970), is another example of how, as Sunderason argues, Abedin revisualizes trauma in such a way that is “an act of resistance” and “an act of collective struggle.”

"Monpura’70," ink on paper, 1970. (Courtesy of Bangladesh National Museum, Dhaka.

Image from Prothom Alo.)

SOMNATH HORE

Somnath Hore (1921-2006), another artist from this time period, came into his own as an artist by drawing posters for the Communist Party of India. His sketches were sometimes accompanied by text and were published in People’s War and in Janayuddha starting in July 1944 and throughout 1944 to 1945. Hore was exposed to the famine by touring through famine-stricken Bengal with Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, then his mentor, for his work in People’s War. It would be during this tour that he would learn about the Communist Party’s ethos of using “culture as [a] front, art as [a] weapon, artists as cultural workers, and touring collectives of performers as cultural squads.”Within his work, Hore was particularly invested in how the collective trauma of starvation affected generations of lands, bodies, and identities. His work is described by scholar Babli Sinha to be a method of “visual reportage [which] combined text and images within the didactic and activist role that the [Communist Party] played”; furthermore, his posters reached rural and illiterate people through “experimental modes of distribution, exhibiting posters in villages and small towns.”Though no attainable records of Hore’s famine works exist today, Hore’s famine experiences inform his post-famine practices. After World War 2, Hore was sent by the Communist Party to observe the Tebhaga labor movement of 1946-47, which he documented in his Tebhaga Diary; he also observed tea plantation activism in his Tea-Garden Journal. Both breadths of work show an emphasis on the agency of activists. After the famine, thanks to the active patronage of Communist Party leaders, Hore was admitted to the Government College of Art in 1945, where he had Zainul Abedin as one of his teachers and trained in woodcut and printmaking. When the Communist Party was banned once again in 1948, Hore was compelled to go underground; he then resurfaced in 1950 and centered on peasant-life and mass movements as a “people’s artist,” working with subject matters like the teachers’ agitation movement and journalists’ strikes.Later, an overall reflection on his experiences and discontent with art would lead Hore to adapt in style, as he noted that “...the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, [and] the horrors of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on [his] style, ‘til there came a time when whatever [he] did, [his work] would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme — the figures and features of the deprived, the destitute, and the abandoned converging on us from all directions.” As a result, Hore would begin to produce pulp prints in a series titled “Wounds.”As termed by scholar Nikhil Sarkar, all three artists — Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Zainul Abedin, and Somnath Hore — continued to document “mass experiences” that occurred after the famine, including that of partition and other activism efforts. In Hore's case, he recorded the Tebhaga movement from 1946 to 1947 in his Tebhaga Diary and worked with several other “mass experiences,” including that of journalists’ strikes and tea plantation workers’ movements. As all three artists dealt with these various “mass experiences,” they also channeled their work through various mediums. For example, along with his pulp prints, Hore was also to produce humanistic, hollow bronze sculptures, though he also worked with oil paint, woodcut, linocut, and lithography.

"Wound 4," pulp print, 1970.(Courtesy of Akar Prakar Gallery.)

Wound 4 is an example of how trauma from events like the famine can mold one’s ability to process their famine (and post-famine) memories. The power of this piece comes from its physicality, where the texture of the work summons the imagery of the artist digging at the surface of the canvas with their bare hands, creating a sense of tension and suggesting the impression that some sort of physical struggle between the artist and artwork has occurred. By using clay and wax to create jagged imperfections onto an otherwise-pristine surface, Hore uses the metaphor of a scar on the canvas to create a dialogue about how long-term memory can be marred from devastating events like the famine.It is also important to note that this work was not made until 1970, nearly thirty years after the famine — as if Hore is claiming that thirty years after the famine, his memory of the famine evokes nothing but agony.Works like Wound 4 also operate in the same manner as works like Abedin’s sketches, in the sense that they are both documentative pieces. However, while Abedin’s pieces document visual sights, Hore’s work captures the tangible aspects of cultural memory, and could also be a testament to how general trauma can impact a social group’s cultural memory. When considering a memory, the blemishes that remain are what shape the interpretations of the memory, and may work to emphasize certain hardships felt during an event. Similarly, for the Bengali people, the long-lasting devastation that directly impacted Bengali communities is what shapes the discussion and language surrounding the famine and post-famine events — an emphasis will naturally be placed on pain, creating a common vocabulary for the Bengali people to use as other cultural memories are forged from “future” traumatic happenings (like the 1947 partition of India and the 1971 Liberation War).

Somnath Hore’s various works. (Courtesy of DAG Modern and Artamour.)Top left: Riots, bronze sculpture

Middle left: Untitled, bronze sculpture

Bottom left: Mother and Child, bronze sculpture

Top right: Wounds 37, pulp print, 1977

Bottom right: Wounds 54, pulp print, 1983